Nominally Hedged | July 2025

ABS, MESOs, and MiniMills: Three Ways to Outrun the Marginal Barrel

When PDPs Become Debt Products: The Real Arbitrage in Oil M&A

Sell side advising was the bread and butter work of my last firm (and our other firm, Ante). We represented a lot of tech companies. These were fun. Not because they had strong cash flow (they didn’t), or because they had rational investors (also no), but because they had one thing the market couldn’t get enough of: growth. TAM slides, go-to-market models, S-curve adoption charts—every engagement felt like pitching a very expensive storybook about the future.

Oil & Gas is not that. Valuing an O&G company in 2025 is the financial equivalent of doing a crossword puzzle where all the answers are already penciled in. There are only two variables that matter: PUDs (proved undeveloped reserves) and PDPs (proved developed producing). And both have been poked, prodded, logged, modelled, and rehashed so many times that most of the value disagreement has evaporated.

Everyone knows the type curves. Everyone knows the spacing. Everyone has access to strip pricing. You can model a PDP’s decline with a middle-school regression. In other words: revenue forecasting is no longer a competitive sport—it’s a commodity. Which means there are really only two things that separate winners from losers in asset M&A:

Cost Structure – If you can slot a peer’s assets into your own ops with better fixed cost absorption or lower LOE, you can squeeze out more margin. This was the entire theme of the 2022–2023 consolidation wave.

Cost of Capital – The more important (but less understood) lever. O&G assets are slow burn: revenue trickles in over 15–30 years. So the lower your discount rate, the more of that future cash flow you can afford to pay for today. Cheaper capital = higher bid.

This second point explains almost everything about the current landscape: Why Japanese conglomerates are outbidding everyone for gas assets? Cost of capital. Why PE-backed operators are holding bags of PDPs they can’t exit? Cost of capital. Why the big post-merger spinout wave hasn’t materialized? Cost of capital. (Also: math.)

You can’t make PDPs work on a 20% IRR hurdle unless you buy them at a garage sale or know something about the subsurface no one else does. And spoiler: if you’re in year 13 of the shale cycle, you probably don’t.

Which brings us to Diversified Energy’s latest financial sleight of hand. DEC just inked a $2B asset-backed securities (ABS) facility with Carlyle. Which sounds boring, but is actually kind of wild. They didn’t raise equity. They didn’t issue 10% high-yield notes. They securitized their gas wells.

Yes, like mortgages. Here’s how it works:

Take a pool of low-decline, producing wells.

Ring-fence them in an SPV (so no one else can touch them).

Structure the cash flows into tranches.

Carlyle buys both the senior and equity slices.

DEC operates the wells, collects a servicing fee, and splits the excess cash flow 50/50.

Eventually, they buy Carlyle out. In the meantime, they fund at ~6.5% and go hunting.

And this matters. Because capital isn’t just capital—it’s a weapon. Let’s play the M&A math game.

Say there’s a PDP asset producing $50M/year in EBITDA. A private equity buyer targeting a 20% IRR can maybe pay $300M and feel good. DEC, funding at 6.5%, can justify $450M–500M and still hit its hurdle. That’s not a small edge. That’s the difference between winning and losing the deal.

Here’s the cost of capital stack in real life:

ABS (DEC’s facility): ~6.5%

High-Yield Debt: ~10%

Private Credit: 11–13% + origination fees

Public Equity: 14–18% implied cost

Private Equity: 15–20%+ IRR targets

So if PDP cash flow is the commodity, the real arbitrage is in how cheaply you can buy it. DEC isn’t just outbidding the field—they’re out-discounting them. Everyone else sees a slow annuity. DEC sees a fixed-income product they can tranche and sell.

That’s why this matters. Not because ABS is new—it’s not. But because DEC is the only one acting like it’s an institutional-grade asset allocator instead of a small-cap E&P. They turned natural gas into a mortgage bond. That’s not just clever. It’s structured finance with a knife in its teeth. All they need now is Ryan Gosling in a pinstripe suit to explain it to a confused room of bankers.

And now the kicker: at Kalibr, we care because cost of capital isn’t just a financial input—it’s a strategic lever that touches everything.

Service providers, for instance, crave revenue certainty. If we know DEC is going to keep acquiring—and we do—then a sourcing strategy can be built around that. Preferred vendor programs. ROFRs. Volume commitments across basins. All designed to trade future optionality for present value.

Want to sweeten the pot? Build a vendor summit. Give your strategic suppliers first-look intel on basin activity, upcoming bids, and commercial signals. Create dependency. Monetize that information advantage.

Because in a world where every molecule is priced the same, the only thing that matters is what you can build on top of it. And cost of capital—when structured this well—is the foundation.

So yes, DEC just turned gas wells into bonds. But more importantly, they turned balance sheet design into a competitive strategy. Everyone else should take notes—or better yet, find someone who knows how to turn a PDP into a prospectus.

The Single-Issue Trap: Why M&A Deals (and Compression Contracts) Quietly Fall Apart

Back to M&A for a minute. One of the most reliable ways to destroy value in a transaction is to get laser-focused on one number — valuation — and ignore the long list of terms that actually determine what you walk away with.

Here’s how that plays out:

A seller sees a headline number they like, signs the LOI quickly, and locks in price before locking in anything else. Diligence begins, and now comes the rest — how long the seller has to stay, what compensation looks like, who else from the team stays, whether earnouts are real or theoretical. But the buyer knows the leverage has shifted. The seller’s alternatives have narrowed. Each point gets negotiated in isolation. By the time it closes, the deal looks nothing like the number that got everyone excited in the first place.

Now apply that logic to Oil & Gas contracts. An operator awards work based on the lowest price, only to realize later that uptime, redundancy, and performance matter far more to the actual value delivered. But by then, it’s too late to negotiate. Worse, many never even try — not because they’re satisfied, but because they assume the field is too thin to create real options.

That’s not a lack of opportunity. That’s a lack of preparation.

At Kalibr, we approach this differently. We drive integrative negotiations early — when leverage is highest — using Multiple Equivalent Simultaneous Offers (MESOs). We don’t treat price as the negotiation. It’s one variable in a broader equation of value, risk, and strategic control.

Take compression, for example. If your negotiation stops at $/month, you’re underutilizing your leverage. Here are a few of the terms we regularly bring into play:

Uptime guarantees — 99% minimum, with automatic credits for underperformance or opt-out rights after three months of noncompliance.

Facility investment — capital commitments from the vendor to expand or upgrade service capabilities.

Redundant part coverage — conex-stocked inventory tied to horsepower, ensuring availability and scope clarity.

Personnel standards — minimum qualifications, experience thresholds, and escalation protocols.

DEMOB cost absorption — challenger vendors covering the cost of displacing the incumbent.

Opt-out clauses — contractual exit rights with clear triggers and demobilization terms.

First rights of refusal — on new units or field expansions, to preserve optionality.

Each one of these affects cash flow, operational stability, or future strategic flexibility. And none of them show up in a simple price comparison.

So when someone says, “We stick with Vendor X because they’re the only ones who know our system,” we tend to ask a few more questions. Like: have you defined what performance looks like? Have you made the terms portable? Have you tested the market? If not, you’re not in a relationship — you’re in a dependency.

Value is rarely lost in a single bad number. It erodes slowly across dozens of unexamined terms. The key is to broaden the negotiation before it narrows on you. You don’t need more suppliers — you need more leverage. And that starts upstream, not when the ink is already dry.

MiniMills, Marginal Barrels, and Why Vendor Leverage is a Market Signal

From time to time, I like borrowing from other industries to make sense of Oil & Gas. Not because energy executives secretly want to run tech companies (though, let’s be honest, some do), but because industrial market structure tends to rhyme. Especially when capital costs, cyclicality, and supply curves are doing the talking.

So let’s talk about steel.

For decades, steel was the domain of integrated mills—enormous, capital-intensive plants that took iron ore and turned it into sheet. They were beautiful in the way only heavily subsidized, high-fixed-cost industrial assets can be. To understand the economics of these plants, you had to think in terms of nominal supply: the theoretical production capacity sitting somewhere to the right on the global supply curve. Think of that as the horizontal bar of steel tons—some of it cheap, some of it not-so-cheap, and the U.S. often somewhere near the edge of viability.

Enter MiniMills. They didn’t try to beat the best steelmakers in the world. They just had to outlast the worst. Using scrap, operating with lean capex, and built for flexibility, MiniMills entered the low-margin rebar business—the stuff no one else really wanted to defend—and slowly started taking share. When demand fell, the marginal producers (the ones furthest right on the supply curve) blinked first. MiniMills stuck around. Then they moved upstream into higher-value segments, one tail at a time.

Now, hold that thought.

Because in 2025, U.S. oil and gas looks a lot like the old steel business. American shale is the marginal barrel. OPEC+ is the left side of the curve. E&Ps here are managing capital like they’ve got a retirement plan to fund—buybacks, dividends, and low leverage have replaced growth at any cost. And all of it is happening in a world where “through-cycle durability” is the investor obsession du jour.

So everyone’s busy trying to prove they sit to the left of the nominal supply curve—i.e., they’ll still be around if WTI drops $20. And to be fair, that’s a good story to tell. But while we’re busy sorting out which operators have real staying power, no one asks the obvious follow-up:

What about the vendors on the other side of the table?

Let me be blunt: I think the hardest job in public markets today might belong to Oilfield Service (OFS) CEOs. They have to walk the same capital discipline line E&Ps are walking—return capital, reduce debt, signal margin expansion—except their revenue is built on hope, not hedged production. They’re in a commoditized business, selling to buyers who increasingly treat them like a utility, and still have to convince investors they’re differentiated.

Which makes them… desperate? No. But let’s just say: motivated.

And that motivation is leverage—yours, if you know how to use it.

If you’re an operator who can offer some predictability, or some duration, or even just a cleaner signal than your peers, you should be extracting value. The keyword here is relative. It doesn’t matter if you’re maintaining activity—it matters if you’re maintaining activity when others aren’t. That’s when your work becomes strategic. That’s when service providers will negotiate with something other than boilerplate.

This is why Kalibr tracks operator stability over time. Not just rig counts or completion activity, but how consistent you actually are through cycles, and how that consistency compares to your peer set. Why? Because when things slow down—or speed up—the data tells you exactly when your leverage is peaking.

And this is just one dimension. We track dozens. Think of it as a leverage-matching game: what attributes make you different, and which ones matter most to the vendor you’re sitting across from? Maybe it’s basin diversity. Maybe it’s velocity. Maybe it’s contract term length, cash conversion, or inventory turn. The magic is in aligning your strongest signal to what the other side is most desperate to hear. That’s how you move markets in a commoditized industry. Maximum differentiation, maximally deployed.

Here’s what we’re seeing:

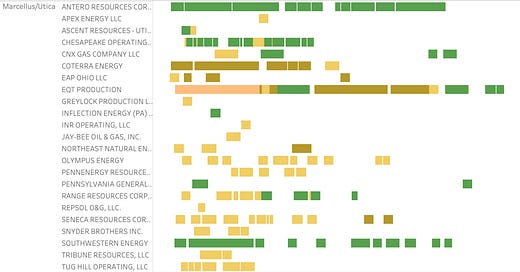

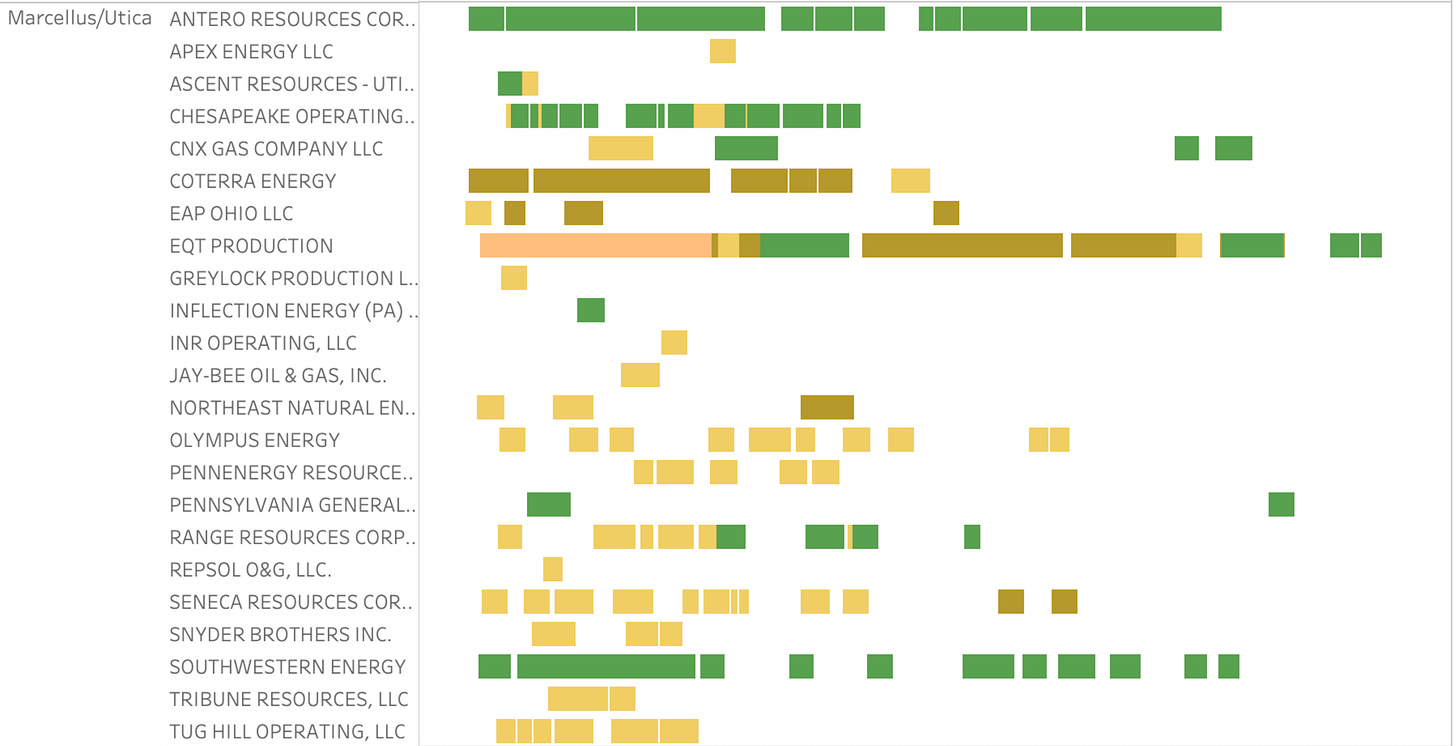

Marcellus/Utica

No surprises here—EQT and Antero sit at the top. Antero advertises their capital intensity efficiency like it’s a brand campaign. EQT’s been singing the through-cycle hymn for a while now. But look closer: Antero shows sustained, stable activity with a single service provider. EQT? More mixed. That kind of consistency matters—not just to investors, but to vendors who might be choosing which client gets the “A team” next quarter.

Powder River Basin (PRB)

The PRB generally sits further right on the supply curve, so any stability there is even more valuable. Anschutz stands out in a big way. In a basin that doesn’t guarantee survival in a downcycle, they’ve built a profile that suggests longevity—and that buys them a different kind of negotiating position.

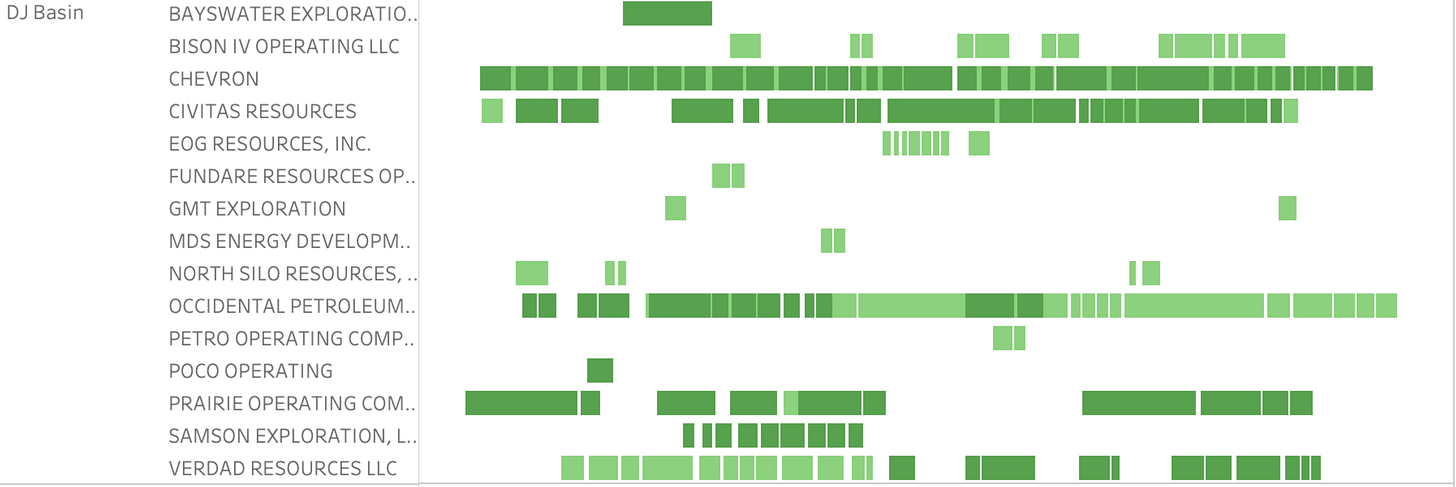

DJ Basin

The DJ is a different beast. Simpler drilling. Lower well costs. But that simplicity can be a curse: if your cost structure is backloaded into completions, it’s harder to spread activity over time. Still, the big names—Chevron and Oxy—show the clearest signal. What’s interesting here isn’t just their activity levels. It’s the absence of service provider churn. When a company doesn’t switch partners every six months, it’s not because they’re lazy. It’s because they don’t have to.

All of this folds into a bigger point: leverage isn’t something you declare—it’s something you prove. And when the market shifts, the operators with multidimensional leverage, peer-relative intelligence, and timing precision will extract more value than the ones who simply claim to be “active.”

Because at the end of the day, MiniMills didn’t win by being perfect. They won by staying in the game when everyone else pulled back. They turned reliability into market power.

Oil & Gas is no different. If you want to sit left of the curve, act like it. Not just with your investors—but with your vendors.

And if you can’t? You’re someone else’s margin.